It fell to me to tell the bees,

though I had wanted another duty—

to be the scribbler at his death,

there chart the third day's quickening.

But fate said no, it falls to you

to tell the bees, the middle daughter.

So it was written at your birth.

I wanted to keep the fire, working

the constant arranging and shifting

of the coals blown flaring,

my cheeks flushed red,

my bed laid down before the fire,

myself anonymous among the strangers

there who'd come and go.

But destiny said no. It falls

to you to tell the bees, it said.

I wanted to be the one to wash his linens,

boiling the death-soiled sheets,

using the waters for my tea.

I might have been the one to seal

his solitude with mud and thatch and string,

the webs he parted every morning,

the hounds' hair combed from brushes,

the dust swept into piles with sparrows' feathers.

Who makes the laws that live

inside the brick and mortar of a name,

selects the seeds, garden or wild,

brings forth the foliage grown up around it

through drought or blight or blossom,

the honey darkening in the bitter years,

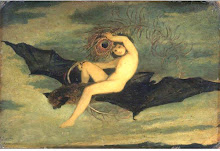

the combs like funeral lace or wedding veils

steeped in oak gall and rainwater,

sequined of rent wings.

And so arrayed I set out, this once

obedient, toward the hives' domed skeps

on evening's hill, five tombs alight.

I thought I heard the thrash and moaning

of confinement, beyond the century,

a calling across dreams,

as if asked to make haste just out of sleep.

I knelt and waited.

The voice that found me gave the news.

Up flew the bees toward his orchards.

By Deborah Digges

The Powers whose name and shape no living creature knows

The Powers whose name and shape no living creature knows

Dim Powers of drowsy thought, let her no longer be

Dim Powers of drowsy thought, let her no longer be